Robert McAlister’s latest book: “North Island, A History”

By Jason Lesley

COASTAL OBSERVER

North Island was a perfect place for wealthy slave owners to escape the misery of their plantations during summer months. By 1820 more than 100 beach houses, a school and a church were built in a village named for the remote island’s most famous visitor, French nobleman Gilbert du Motier de Lafayette, at the beginning of the Revolutionary War.

Plantation owners took their most docile servants and all the household finery necessary to maintain their lifestyle by boat to a summer playground of ocean breezes and cool surf free from mosquitoes and the oppressive humidity of the rice fields. The island’s remoteness made it perfect for maintaining a population of 300 slaves in the summer. There was no escape.

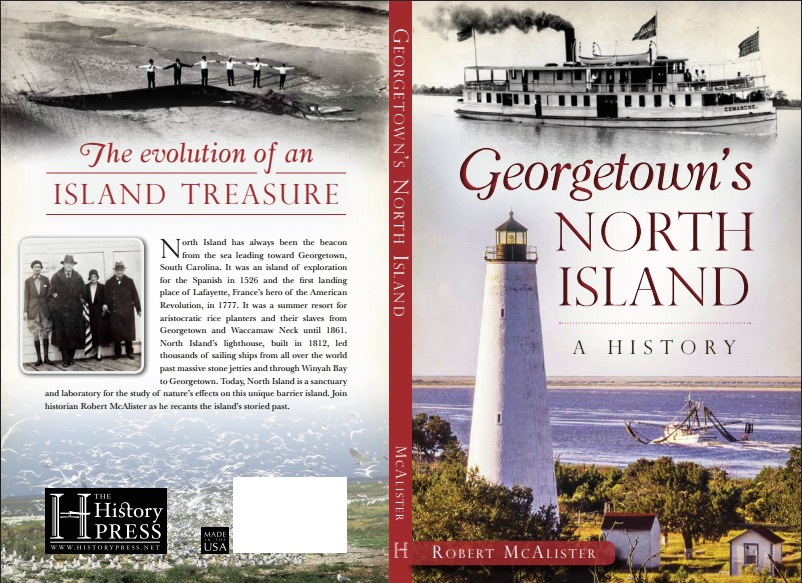

Author Robert McAlister has written “Georgetown’s North Island, A History” that explains how the northernmost sea island in a chain extending to the northern border of Florida went from being a summer resort for the wealthy to a protected wilderness. North Island is 9 miles long with gently sloping sandy beaches, a shallow entrance into Winyah Bay on its south side, narrow creeks and wide salt marshes on its west side and a second small inlet from the ocean known as North Inlet at its north end. North Inlet leads to a pristine basin fed by the Atlantic Ocean and creeks connecting to Winyah Bay. Most of the island is less than a half-mile wide but increases to almost a mile at its south end. Behind the ocean beaches are sand dunes and ridges — some more than 40 feet high — and maritime forests of pine, cedar, palmetto and live oak extending back to the salt marshes.

Native American’s left clay and stone pottery shards on North Island as proof they were there. Spanish explorers built houses in 1526, intending to establish a colony. During the summer, malaria took the lives of many of the Spaniards, including leader Lucas Vazquez de Allyon. Starvation, strife with local natives and disappointment over not finding gold led the Spaniards to abandon the settlement and return to Hispaniola in early 1527.

With the declaration of Georgetown as a port of entry in 1733, North Island became home to a few harbor pilots whose job it was to guide ships across the Winyah Bay sandbar and up the bay.

McAlister includes an entry from the Dec. 11, 1762, Georgetown Gazette about a Spanish privateer sacking the house of the harbor pilot and stealing his sloop. A foreign visitor on June 12, 1777, was more welcome. A two-masted, square-rigged sailing vessel furled its sails and anchored south of North Island. It showed French colors and the name La Victorie at its stern. A jolly boat was launched from the ship with 10 men rowing north along the deserted beach. They reached a narrow inlet at the northern tip of the island and, by moonlight, saw four slaves digging oysters. With their jolly boat stuck in the mud, the Frenchmen climbed into the slaves’ canoe and were taken to the house of their master, Major Benjamin Huger, who offered what Lafayette later described as “a cordial welcome and generous hospitality.”

Huger told the Frenchmen that Winyah Bay was too shallow for their ship and promised to find a pilot to guide it to Charles Town. He urged Lafayette to travel by land to avoid being captured at sea by the British.

A free America did not mean freedom for all. The men of Lafayette Village were united in their support of an aristocratic republic and had the power to control their state. They opposed any federal intrusions that might limit slavery and talked in hushed tones about the murder of a Black River planter in May 1821 by escaped slaves.

The isolation of North Island allowed planters exceptional control of their summer slaves, but it proved fatal in 1822 when a hurricane’s storm surge nearly covered the island. “The planters and their families climbed to the roofs of their houses or swam and ran toward the safety of higher ground,” McAlister wrote. “There were high sand dunes on the island, but they were far away from Lafayette Village. Many of the slaves, who were trapped in their rooms under the masters’ houses had no place to go and were either drowned by the ocean surge or washed out to sea. Approximately 120 slaves on North Island were lost. Some of them were children, and others were midwives who had nursed the children of planters.”

McAlister includes a number of vivid accounts of the 1822 hurricane that claimed more than 300 lives in all. The planters had their houses rebuilt and life went on the way it had for decades. The summer population would swell to nearly 700, according to one account, and a new church was built in 1826.

No storm could rival the Civil War for its effects on North Island. By 1860 there were 18,000 slaves and only 2,000 whites in the Georgetown District. Planters were dependent on a slave economy, and the election of Abraham Lincoln triggered South Carolina’s secession from the Union.

Confederate troops abandoned the defense of North and South islands, and in May 1862 Union ships sailed up the Waccamaw River to rice plantations where they took 80 slaves on board as contraband and transported them to North Island. Hundreds of slaves were removed from plantations and quartered on North Island, but food was scarce and soldiers treated them little better than overseers in the rice fields. Most were transferred to the Union base at Port Royal where they joined the Union Army or were put to work in camps.

The end of the rice economy left planters impoverished for decades. Summer houses blown away by hurricanes couldn’t be replaced. In 1884 because of unpaid taxes, North Island, South Island and part of Cat Island were sold to retired Civil War general E.P. Alexander, who had visited the island to hunt and fish in the early 1880s.

Alexander sold 8,000 acres on North Island to Michigan lumber and mining industrialist J.L. Wheeler in 1909. After Alexander’s death in 1910, Detroit playboy Bill Yawkey, son of deceased lumber tycoon William Yawkey, bought 20,000 acres on South Island and Cat Island. He eventually bought North Island from Wheeler and his partner Richard Cartwright.

Bill Yawkey adopted his orphaned nephew Tom Yawkey in 1909 and left him an estate of $7 million and most of his South Carolina property when he died in 1918. He bought North Island from Bill Yawkey’s widow, Margaret, in 1933 when he became eligible for his inheritance.

Tom Yawkey built a rough hunting lodge on North Island, but his primary winter residence was on South Island. When he died in 1976 he left his 20,000-acre endowed estate to the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. Yawkey’s will says North Island is to be used for all time as a wilderness area without permanent structures or human habitation and without roads of any sort. The Tom Yawkey Wildlife Center consists of land on Cat Island, South Island and most of North Island. It was one of the largest conservation grants in U.S. history.

McAlister includes every interesting tidbit of information he found on North Island, from presidential hunting trips to barbecues on the beach by a party crowd that elected an island mayor. Photos made by former Yawkey Center biologist Phil Wilkinson, maps and entries from the Georgetown County Digital Library enhance the book’s presentation.

Copies of “Georgetown’s North Island, A History” are available at the South Carolina Maritime Museum or at historypress.net for $21.99.