Veteran diver, Pete Manchee, discusses shipwrecks near Georgetown

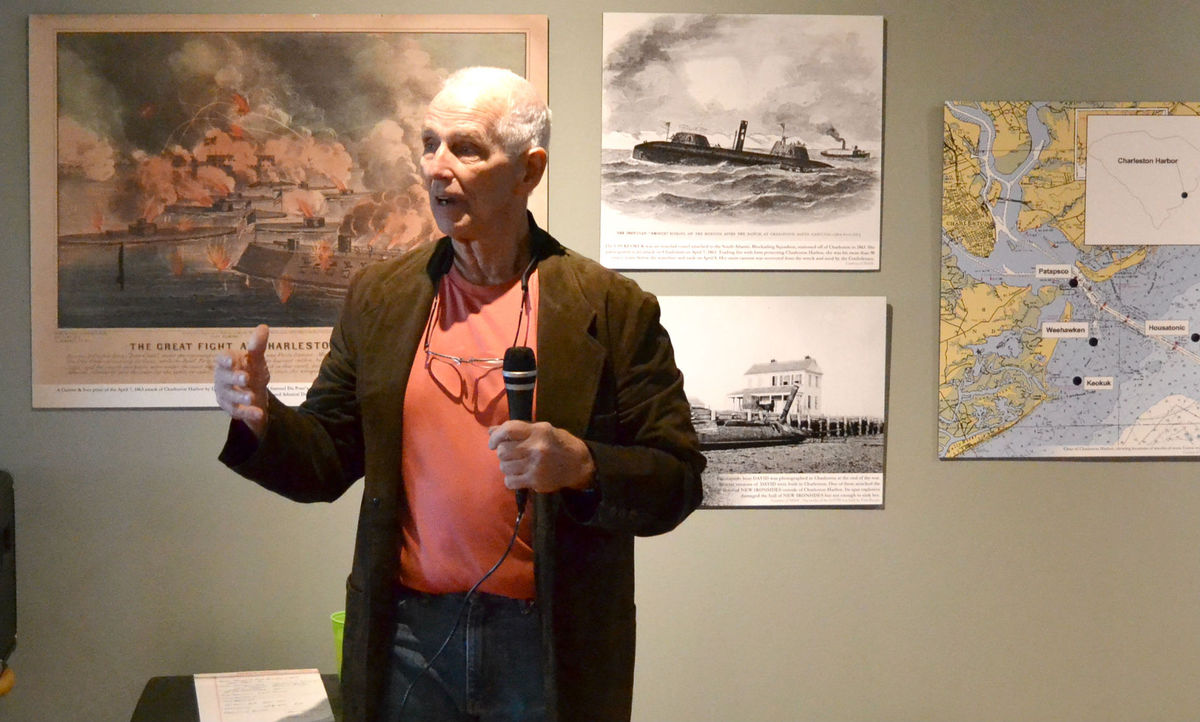

Pete Manchee speaks about his decades worth of shipwreck diving during an event at the S.C. Maritime Museum in Georgetown Jan. 24.

Pete Manchee speaks about his decades worth of shipwreck diving during an event at the S.C. Maritime Museum in Georgetown Jan. 24.

Story and photos by David Purtell/South Strand News

Beneath the waves, the sea holds the wreckage of countless ships lost to time and memory. But many others have been found, and their wreckage provides a frozen glimpse into the past.

Pete Manchee has spent his life searching for and exploring shipwrecks around the world. He shared the stories of a handful of ships resting in waters off the Carolina coast during an event Wednesday [January 24, 2018] at the South Carolina Maritime Museum.

Manchee, a professional diver and founding member of the museum, spoke to around 100 people about his experience diving the wrecks of four ships: The HMS Saint Cathan and the Hebe, the City of Richmond and the Ringborg — models of the ships and some of their artifacts are currently on display in the museum’s shipwreck exhibit.

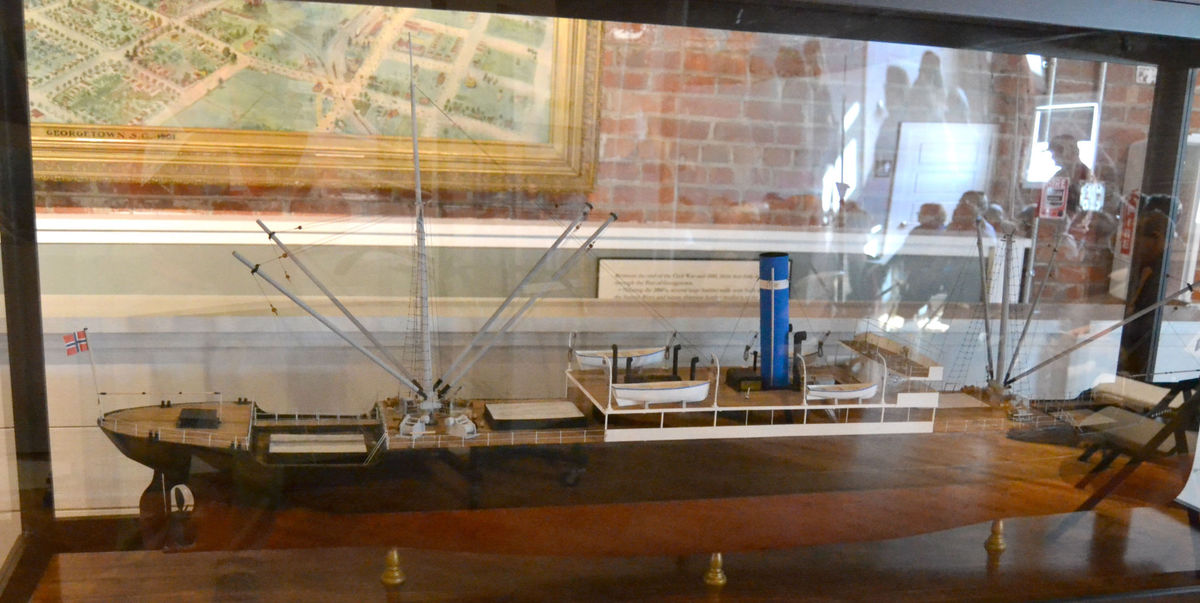

A model of the HMS Saint Cathan, which sank off the Carolina coast during World War II.

A model of the HMS Saint Cathan, which sank off the Carolina coast during World War II.

Saint Cathan and the Hebe

During World War II, the Saint Cathan, a converted trawler, was stationed at the Naval base in Charleston and hunted German submarines, known as U-boats. In April 1942, the Saint Cathan, with 39 British sailors onboard, and another ship were searching for a U-boat reported in the area of Frying Pan Shoals off Cape Fear.

“They chugged out of Charleston Harbor and headed northeast toward the contact,” Manchee said. But during the voyage, the two ships got separated. Meanwhile, the Hebe, a cargo ship from New York, was heading south on its way to South America.

It was a dark night, Manchee said, and the lookouts on the Hebe were not paying attention. The ship ran into the Saint Cathan.

“She went down in about four or five minutes” in about 110 feet of water, Manchee said about the Cathan. Only nine of its crew survived. The Hebe sank in about 25 minutes, but all of its crew lived.

Manchee, a New Jersey native who graduated from the University of South Carolina, started exploring the wrecks in the 1980s. He said discovering many wrecks is a result of making friends with fishermen.

“Fishermen are the guys that really find wrecks. They’re out there everyday, commercial fishing,” he said. “And they know when they go over an area that’s loaded with fish that there’s a good chance the fish are attracted by a wreck.”

A government inquiry found the Hebe was 25 miles farther out to see than it should’ve been. During the war, sea lanes were established close to shore to deter attacks by U-boats.

A model of the Hebe.

A model of the Hebe.

The City of Richmond

The ship was built in 1913 and was a luxury vessel sailing in the Chesapeake Bay area.

“All of her chefs were gourmet chefs,” Manchee said, adding he’s met people who were passengers on the ship as children. After World War II, it was the first commercial ship to use radar.

In the 1960s, it was sold to a company that wanted to use it in the Caribbean. “Turn it into a floating hotel, restaurant, bar, dance club,” Manchee said.

It left Norfolk, Virginia, under tow in October 1965 with an inexperienced six-man crew.

“Well, they ran into some rough weather,” Manchee said, and the crew didn’t know how to handle the ship in the high seas. The ship started to list, and the situation grew worse as the cargo started to shift.

“Long story short … the vessel sinks in 55-60 feet of water” off Georgetown, Manchee said.

The ship’s three upper decks were made of wood, and after the ship had sunk the built up air pressure caused the decks to explode.

A model of the S.S. City of Richmond.

Manchee, whose first dive off the South Carolina was in the late 1960s, said something divers search for is the nice dinnerware on wrecks such as the City of Richmond.

The Ringborg

The ship was a tramp freighter built in 1906 in the Netherlands. It went all over the world carrying cargo before sinking off Cape Fear during a storm in 1924. But when Manchee started diving it in the 1980s, nobody know what ship it was.

A model of the Ringborg

A model of the Ringborg

“I’m as interested in the doing the detective work to figure out what that vessel is as I am to dive it,” Manchee said. In 1989, he and other divers recovered the ship’s brass helm, which is on display at the museum.

But it wasn’t until 2007 that the ship was identified through efforts by Manchee and his peers. The ship Ringborg was recorded in volumes of shipwrecks, but the location listed was 150 miles away from the actual site of the wreck. The connection was made after Manchee found an article about the wreck from the Charleston News and Courier.

“So we knew right then, 18 years after we started looking, that it was the Ringborg,” Manchee said.

Manchee said one thing complicating the search was that the ship had three different names during its career.

“Even today, believe it or not, I have people call me and say, ‘I don’t think it’s the Ringborg,” Manchee said.

But nobody has proved him wrong.

The event Wednesday was the first in a new series the museum plans to hold at its renovated building on Front Street.