New Exhibit: the History of Fishing

Hook, line and history

By Jason Lesley

Coastal Observer

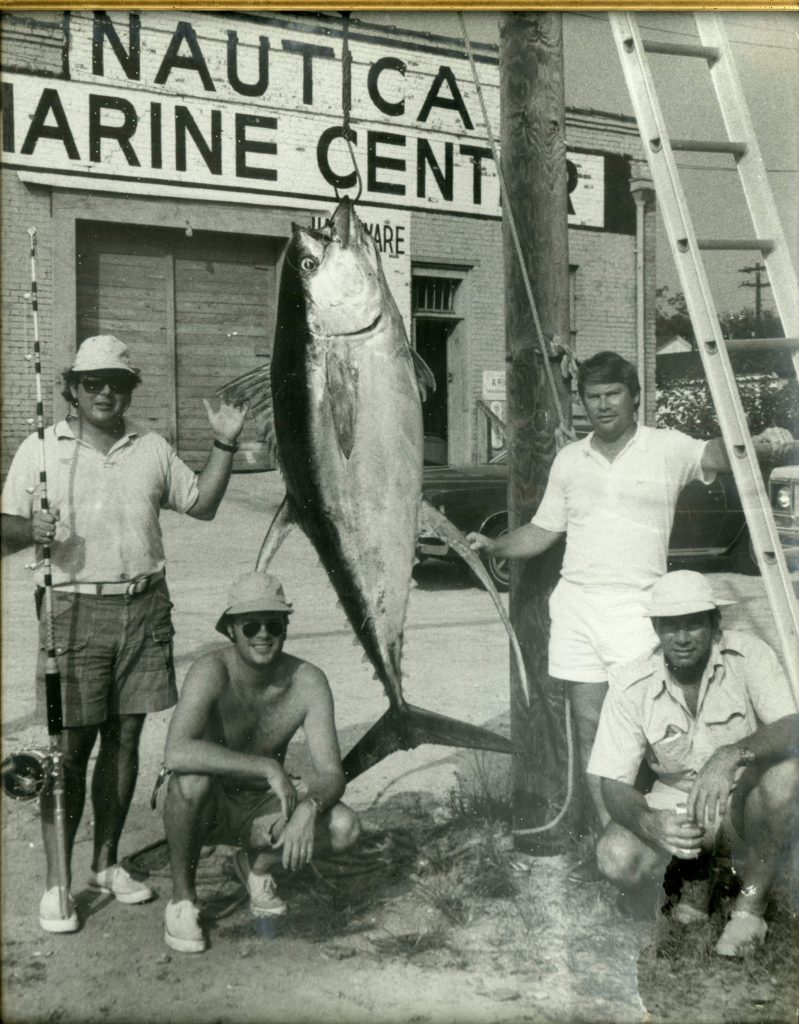

A black-and-white photo in the new exhibit at the South Carolina Maritime Museum shows Bony Peace, Jim Johnston, Stone Miller and Wallace Pate enjoying the moment after catching a record yellowfin tuna on their boat, Jackpot, in 1974. Happy times.

The picture is among dozens of snapshots of anglers and their trophy fish on display at the Front Street museum’s “History of Fishing” exhibit that has opened just in time for this week’s Bassmaster Elite fishing tournament in Georgetown.

“History of Fishing” may be a bit of an overstatement for the exhibit. Fish have been caught in places other than Georgetown, but few in America have a 300-year history of hooks, lines and sinkers that is much better.

Yellowfin tuna, like the big one caught on the boat Jackpot in ’74, is an example of why people should pay attention to the history of fishing. Even disappointed marlin fishermen usually returned to Georgetown with a tuna or two in years past. Dean Cain of the Marine Resources Division of the S.C. Department of Natural Resources in Charleston said only six were caught in South Carolina waters last year. They’ve moved 300 miles out to sea, where longliners are catching them.

He’s hoping yellowfin tuna don’t join the Atlantic sturgeon and the shad that were pillars of the Georgetown economy until they were nearly fished into extinction. “Many species have dwindled,” Cain told people gathered for a luncheon at the museum last week to open the exhibit.

Commercial fishing has been around since settlers came to Georgetown and found sturgeon and shad easy to catch in nets. “You could fill a big room with shad in a short time,” Cain said. Fishermen floated flat-bottom boats up the Waccamaw and filled them with fish, he said.

As usual, where something is plentiful there is waste. It became so common for fishermen to butcher sturgeon, some weighing as much as 700 pounds, on the shores of the Sampit River that Georgetown Mayor William Doyle Morgan began enforcing a law making it illegal within 3 miles of the city limits. Fines as high as $50 were threatened. The butchering moved to North Island, and those who thought it was haunted did their dirty work on South Island. Whole fish were left to rot once the roe was extracted.

Most of the exhibit’s photos show smiling Georgetonians wearing coats and ties posing with fishing poles and strings of big redfish or other species. Catching a dozen 30-pounders was considered a good day, judging from the pictures people saved. “They caught them because they could,” said Mac McAllister, museum director, “the same way they killed 150, 200 ducks.”

The exhibit’s true purpose, McAllister said, is to promote conservation of nature while highlighting names from the past that meant so much: Crayton, Cathou, Skinner, Caines, Tarbox and Vereen to name a few.

Still, Georgetown fishermen didn’t put a dent in the fishery until two things arrived around 1900. The gasoline engine turned dozens of Winyah Bay bateaus into fishing machines and the railroad arrived with enough ice to transport shad roe, shrimp and fish to the northern markets.

By 1916 the short-nosed sturgeon was regulated by law and by the mid-40s the Atlantic sturgeon and shad were limited too. Later, longliners devastated the swordfish. Johnston loaned the exhibit a picture of a boat discharging 40,000 pounds of swordfish in Georgetown.

Industrial fishing all but disappeared here with the ban on sturgeon fishing in 1983. “I began working with DNR in 1985,” Cain said, “and I stepped into a wasp nest. They had just closed these guys’ fishery. They got a lot of money off sturgeon.”

Though Cathou’s Fish House remained a place for old-timers to sit around a pot bellied stove, commercial fishermen turned to shrimping and recreational fishing gained a toe hold.

The Vereen family ran the Anne Howe, the first charter boat out of Murrells Inlet, from docks at Oliver’s Lodge. Hucksie Caines had one of the first charter boats in Georgetown, and Wright Skinner Sr. owned the Kerbath, captained by Foster Bourne and docked at South Island.

South Carolina’s deep sea fishing got its start in 1964 when Katherine “Cappy” Fitzgerald brought in a 237-pound blue marlin to the old Esso Dock in Georgetown. The likelihood of landing a blue marlin was so remote at the time that Judge L.K. Dinks had promised to eat it.

The big fish proved revolutionary for Georgetown. Pate formed the first marlin tournament in Georgetown in 1968. Thirteen entrants left from his Nautica Marine dock after weather delayed the event for a week. The next year, eight blues and two whites were caught. Johnston bought the marina from Pate in 1969 and two years later Peace became a partner in the operation.

The tournament became so popular that by 1977, organizers realized too many small billfish were being caught. They changed the rules to encourage catch and release. After a few years at Belle Isle, the tournament found a permanent home at Georgetown Landing Marina. South Carolina Gov. Carroll Campbell, who kept a fishing boat, Second Lady, at Murrells Inlet, established the Governor’s Cup Series in 1988 with Georgetown as one of five locations.

The museum’s exhibit includes the tail from a record 881-pound marlin caught by Mark Rogers.