History: Sunken Union flagship marks 150 years

By Charles Swenson, Coastal Observer

There was fog on Winyah Bay. Fog among the live oaks and silent guns of Battery White. Fog in Georgetown.

At 7:15 a.m., the USS Harvest Moon weighed anchor from off the battery. The tide was rising. The sidewheel steamer was heading to Charleston with Rear Adm. John A. Dahlgren aboard.

The sun had been up for half an hour, but the sky was still a dull gray. Dahlgren, 55, and in command of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, was pacing his cabin. The table had been laid for breakfast. He paused occasionally to look at the shore through a telescope.

It was March 1, 1865. Confederate troops had evacuated Georgetown six days earlier. Battery White had fallen without firing a shot. Dahlgren was trying to make contact with General Sherman’s army, which he expected to drive toward the coast.

The war was all but over. The town council sent the Navy a letter of surrender on Feb. 25. Dahlgren replied with a proclamation that began by stating that slavery was at an end and invited the inhabitants “to return to their ordinary pursuits as peaceable citizens.”

The Harvest Moon’s peacetime pursuit had been carrying passengers and cargo along the coast of Maine, one to which it would never return. The ship remains in Winyah Bay, buried under the silt with just the base of its smokestack still visible above the water.

William Uptegrove had guided Union ships through Winyah Bay since the start of the blockade. His family remained in Georgetown until July 1862, when they were allowed to leave with the Navy under a flag of truce.

Ordered to take the Harvest Moon out to sea, Uptegrove conned the ship down the Marsh Channel, “it being the shortest way to sea, as I supposed the admiral was in haste to get to Charleston,” he explained.

There was a man at the bow with a lead-line, casting it to gauge the channel depth. The Harvest Moon was 193 feet long, but had a draft of just under 8 feet. Coming up from Bulls Bay to Georgetown, it had rolled uncomfortably in the stormy seas, one of the officers said.

But the ship was ideal for the shallow coastal waters along the rivers and bays of the Southeast coast. The Navy had bought the Harvest Moon for $99,300 from its civilian owners, the equivalent of $2.5 million today.

The two sidewheels, 24-feet in diameter, could move the ship at 15 knots, but she was traveling down Winyah Bay at about 6 knots. The channel took her past Frazier’s Point on what is now Hobcaw Barony. The deep water ran farther east than it does today, toward a shallow area known as Mud Bay.

Ensign Alna Bates was officer of the deck and standing forward near the man with the lead-line when he felt a shock. He thought the Harvest Moon had hit a snag, as it had done a few days before near Georgetown.

Dahlgren felt the shock, too. “The partition between the cabin and the wardroom was shattered and driven in towards me, while all loose articles in the cabin flew in different directions,” he wrote in his diary. “Then came the hurried tramp of men’s feet, and a voice of someone in the water was heard shrieking, as if badly hurt.”

Acting Master John K. Crosby, captain of the ship, was in the pilot house. His were among the feet Dahlgren heard. There was “a heavy explosion aft followed by a loud crash,” Crosby told a court of inquiry. “I immediately jumped out of the pilot house and ran aft.”

He found a hole in the deck 10- to 12-feet square, just behind the starboard, or right side, wheel.

It was about 7:45 a.m. The Harvest Moon was about 1,000 feet from the Waccamaw Neck side of the bay.

Ensign William H. Bullis heard the explosion and saw the smokestack shake. He thought one of the two coal-fired boilers had exploded.

“My first notion was that the boilers had burst,” Dahlgren wrote. “Then the smell of burnt gunpowder suggested that the magazine had exploded.”

Patrick McGrath, a sailor, was washing down the starboard deck near the wardroom when the explosion occurred. He thought a gun had burst. It was McGrath’s screams that the admiral heard. He had been knocked overboard.

Second Assistant Engineer James A. Miller had opened his cabin door when a column of water and smoke shot up though the deck 14 feet away. “My first impression was that a shell had exploded,” he told the court of inquiry.

Miller went to the engine room. It had filled with water and the furnaces were out. The one-cylinder engine had made a half dozen turns and stopped.

The Harvest Moon settled on the bottom of the bay. It was not yet 8 a.m.

The coxswain, James Cluney, told the court of inquiry he had no doubt what caused the explosion. “The captain came out of the pilot house and asked what the matter was and I told him that the vessel was struck by a torpedo,” he said.

“I did not expect to run over any torpedoes because I heard that the channel had been partly dragged for torpedoes by the USS Mingoe,” Uptegrove told the court.

The torpedo of the time was not self-propelled. It was what would later be called a mine.

The Navy got word in October 1864 that the Confederates planned to mine Winyah Bay. The one that sank the Harvest Moon is credited to Capt. Thomas W. Daggett, who served in the Waccamaw Light Artillery at the start of the war.

He later joined the 10th South Carolina, which was sent to defend the coast in the waning months of the war.

Daggett was an engineer. He operated the mill at Laurel Hill Plantation, now part of Brookgreen Gardens.

His role in the sinking of the Harvest Moon was handed down through family history.

Stephen W. Roquie owned a store in Georgetown. The building is now part of the Rice Museum. He also served in the 10th South Carolina, but returned home from Mississippi after an illness. In early 1865, he was part of an artillery company posted to Battery White.

The typical torpedo was fashioned from a barrel, packed with gunpowder and triggered with a percussion cap.

Daggett, possibly with Rouquie’s help, reportedly fashioned the torpedo on the second floor of Rouquie’s store.

In reporting the sinking of the Harvest Moon, the superintendent of the Confederacy’s torpdeo bureau, Brig. Gen. Gabriel J. Rains, wrote “This torpedo was left there before our troops evacuated.”

After the sinking, the channel was swept for torpedoes. None were found.

John Hazard joined the Navy in Boston in January 1864, a month before the Harvest Moon left for the South. He was 30. A cook in civilian life. A note lists him as “mulatto.”

Hazard was the wardroom steward on the Harvest Moon. He was below deck when the mine exploded.

The crew was evacuated by the tug Clover to nearby ships. They returned the next morning to find Hazard’s body. He had his initials tatooed on his right forearm.

Hazard’s body was taken ashore for burial the next evening. The grave is unmarked, but there is a silent, rusted memorial nearby in Winyah Bay.

Family tie led engineer to historic ship.

By Charles Swenson Coastal Observer

One Harvest Moon sits under several feet of mud in a shallow corner of Winyah Bay. The other sits behind a quarter of an inch of glass.

One was built by the Joseph Dyer shipyard in Portland, Maine. The other was built by Elliott Smith.

The Union Navy flagship of Admiral John A. Dahlgren has a special place in the Smith family. William Elliott Todd was a third assistant engineer aboard the Harvest Moon when it struck a torpedo and sank in Winyah Bay on March 1, 1865. He is the great-grandfather of Elliott Smith, who has compiled a trove of information about the ship under the umbrella of the Harvest Moon Historical Society.

“I’ve followed it for about 25 years now,” Smith said by phone from his home in Wilmington, Del.

Some of his research found its way into “Defending South Carolina’s Coast,” a 2009 book by Rick Simmons that tells the history of the Civil War along the north coast. Simmons, a South Carolina native who is a professor at Louisiana Tech University, has often seen the smokestack of the Harvest Moon while boating on Winyah Bay. “It’s really an important ship for several reasons,” Simmons said. “It seemed like an ill-fated ship for its short career.”

Todd served on the Harvest Moon only a few weeks. He had written a letter to his brother-in-law, who was also in the Navy, on Feb. 27. Todd found it floating in the wreckage and added a postcript on the back about the sinking. “Had nearly a dozen letters in a letter box and I found this among two others floating around the boat. I suppose they, like most everything else, were blown to the devil by the rebels [sic] delivish engines of destruction,” Todd wrote.

The letter was among the belongings of Smith’s aunt. He found it after her death. “That kind of piqued my interest,” he said.

Smith, like his great-grandfather, is an engineer. He was interested in model building, and his historical research in the Harvest Moon made it inevitable that a model would emerge.

He spent time at the National Archives reading through the ship’s logbook. He found the crew rosters.

Smith posted the information online and that led to connections from other ancestors of Harvest Moon crew.

The ship was only in service about 18 months, but “it was in a lot of important places in the last year of the war,” Simmons said.

Off Savannah, with Gen. Sherman on board, the Harvest Moon ran aground. That allowed Confederate troops to evacuate while Union forces awaited orders.

The acting captain at the time of the sinking had been the officer of the deck on the USS Housatanic when it was sunk by the Confederate submarine CSS Hunley.

“There are so many stories,” Smith said.

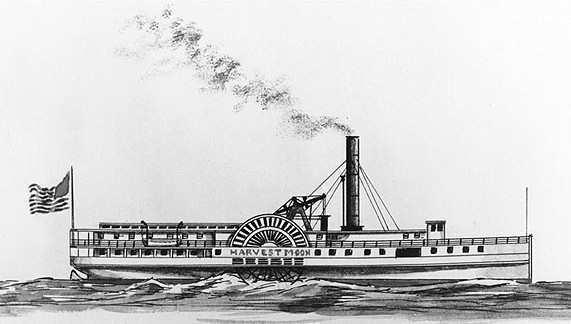

There is one known photo of the ship, and that led Smith to find a photo of a painting of the Harvest Moon by a prominent marine artist. The original painting has never been found.

The image provided additional information for Smith’s model. “I’m reasonably comfortable with the details,” he said. It took him about five months to build.

Over the years there were plans to raise the Harvest Moon, but surveys by the Navy and private divers determined there wasn’t much left to raise. Equipment was removed in the weeks following the sinking.

Smith hopes some timber from the ship may turn up in someone’s home in Georgetown.

“It’s such a great thing,” Simmons said. “How many historical artifacts like this are there?”

The Maritime Museum plans an oyster roast Sunday to commemorate the anniversary of the sinking. Smith would like to get back to Georgetown, but will miss the party.

“I’m going to be in the Caribbean,” he said. “Taking a cruise.”